1789-1914: the war on patois

The war on patois began shortly after the overthrow of the monarchy in 1789. Some saw a national language as one of the great tools which could unify the country. In the spirit of The Enlightenment, some in the new government fervently believed that the installment of a national language would bring égalité* to all men. Further, it was felt that the inability of a majority of a country’s citizens to be unable to understand political debate was undemocratic.

It is somewhat ironic that the choice for a national language should be the king’s tongue, but it is not all that surprising. After all, the new power base would ultimately belong to the français speaking Bourgeoisie who controlled both the merchant shipping and France’s industrial capacity. Under the monarchy, these wealthy businessmen had always pursued equality on their own with the nobility.** That they spoke français was the result of one such failed effort at parity. But despite their superior education, their great social refinement, their powerful positions in business, and sometimes extravagant wealth, they would always be a lesser man than the titled noble. It would take bloodshed to tear down the social structure of birthright.

France was hopelessly behind both England and Germany in terms of industrial development and output, being so deeply invested, both economically and philosophically, in its feudal agricultural economy. But where France did lead was in thought. France was, far and above, the world’s intellectual giant. France’s post-revolution urban elite developed a culture of scholarship that was producing thinkers who were making groundbreaking strides in science, medicine, and philosophy, as well as the arenas of political and economic theory. Education, which these men held dear, was seen as the tool which would simultaneously and seamlessly spread both égalité and français as France.

(*) Égalité was a new term and concept thought to be first used in 1774. (Britannica) Although the leader of the Jacobins, Maximilien de Robespierre, was known to have said this in December 1790: “On their uniforms engraved these words: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité. The same words are inscribed on flags which bear the three colors of the nation.” The notion of judicial égalité was set into French law in Article 6 of the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen de 1789 (the rights of man). It pronounced that law “must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in its eyes, shall be equally eligible to all high offices, public positions and employments, according to their ability, and without other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.“ (frenchmoments.eu/) More on the French motto can be learned here.

(**) Like most men throughout history, equality is rarely sought for all men. The past has taught us that the definition of the term word ‘men’ can be endlessly manipulated or complicated by exceptions. What they had sought was their own ability to stand as equals with the nobility and king. Taking this idea one step further, it would not be a stretch to assume that many of these very wealthy, proud, educated, refined men felt socially and morally superior. They likely did not common, and no doubt resented their ‘commoner’ moniker. In their new empire, they would not speak some lowly country patois. There was really only one choice for a national language. It would be français.

The stigmatization of patois

So, with great intention, the use of patois across France was stigmatized and societally degraded. In the south of France, those who spoke Occitan languages were acutely affected by the French governmental assault on its patois. There it was called Vergonha, or the “shame”. Linguists Jean Léo Léonard & Gilles Barot wrote in 2012, wrote that “to be considered as a ‘patois’ is one of the worse curses that may happen to a language.”

The first and most famous leader in this fight was Cardinal Henri Grégoire, who wrote a report to the revolutionary government calling not only for the institution of français but the “annihilation” of regional patois. For those in Grégoire’s camp, patois was considered to be a force of obscurantism. Obscurantism was an interesting concept that an obscurantist was an “enemy of intellectual enlightenment” and worked against the “diffusion of knowledge” (Wikipedia). The idea was the existence of patois was preventing information from being passed, and thus obscuring facts and details from being known.

Grégoire’s position was clearly extreme, as were many aspects of those revolutionary times, going as far as to write that patois languages were “barbaric jargons and those coarse lingos that can only serve fanatics and counter-revolutionaries now!” However, those who that sought to institute français came to the task with varying viewpoints regarding these dialects. There were those who were overly passionate, like Grégoire, that considered patois vulgar, with the “expression of ignorance, archaic prejudice, and obscenity”(Forrest 1991). But others described it as only capable of expressing simple emotion; be it “anger, hate, or love”. This was a significant slight by those men who cherished intellectual thought. Still, there were others who viewed it with a bit more kindness,“believing it expressed a pastoral simplicity and closeness to nature” (Forrest 1991). To paraphrase Forrest, it was the language that the paysan spoke to his oxen and his dog.

The early 1800s: turbulent politics and war make a national language impossible

But the reality was that the First Republic’s national assembly was deeply divided and had limited time or attention to pursuing Grégoire’s linguistic passions. To this point, the events of the revolution had not disposed of Louis XVI. The king was now sharing power in a constitutional monarchy with the national assembly.

In what seems more of an urgent need for a display of decisive revolutionary change, rather than having instituted a well-conceived plan, the fledgling government restructured the country into 83 new départements in 1791. These new departments were drawn to disrupt as many of the traditional, regional, and ethnic associations as possible, and this included patois. The most highly cited example of separating a major city from its historical homeland is Toulouse. In 1793, Toulouse had a population of 52,612 and was one of France’s largest cities. It was decided to break up the Languedoc by splitting Toulouse off in order to force new Haute-Garonne-centric governmental and trade associations. While these did not sever the natural routes of trade from Toulouse to the Mediterranean coast, it would divide the old political interests that these regions had historically shared. As mentioned earlier, it was these Occitan speakers (langues d’Oc) who would feel the most victimized by these kinds of actions by Paris. But there is little doubt that Paris did make special efforts to bring the sometimes defiant South into the national fold.

The attention of the reformers in Paris was intermittent at best, as upheaval was commonplace in France in the first half of the 1800s. France, from this time forward, would find itself at the center of conflicts involving many nations. War, which many within the national assembly felt would unify a divided France, would now be entered into as a member of an alliance, but what unfolded was a new type of war with an unlimited battlefield. This kind of warfare had its battles spilling outside of Europe, across the open oceans, and in far-flung colonies, intended to disrupt and deprive the enemy of wealth and matériel needed to continue the conflict. The war between the major powers of Europe had taken on a new face, one that would define conflicts for the next 150 years. The term for this kind of battle was total war.

1830-1851: education as a political battlefield

Education, the sword with which Cardinal Grégoire’s war on patois was to have been waged, had already been badly neglected for several decades by the 1830s. It is estimated that in 1835, only one person out of every four hundred thirty-five attended any kind of school within France (Theis, guizot.com). Because of this, the use of patois went along unfettered. But beginning in 1830, with the reign of King Louis-Philippe, attention would be paid to restoring public education in France. Two men, working under two successive monarchies, would institute an expansive system of schools across France. François Guizot would begin the work in 1832, slowly breaking down many political barriers to the establishment of education. The second man, Frédéric-Alfred-Pierre, who is better known by his noble title comté de Falloux du Coudray, would finish re-instituting an educational system in 1849. Although at this juncture, there was no pointed assault on patois, the establishment of a robust system of schools meant that students all across France were now learning and spreading the langues français into their communities.

It was Guizot who did the heavy lifting in the redevelopment of schools in France. Guizot’s significant reputation as a great professor and statesman eventually allowed him to negotiate the deep political divides between the conservative monarchist and the secular Republicans. Both groups were equally intransigent in their positions regarding the role of the church in education, and the success of the implementation of any educational system was the result of years of mediation and compromise. In the end, a level of Church’s involvement in education was grudgingly agreed accepted by the Republicans in the assembly. Guizot’s accomplishment of instituting instruction for boys in communities with over 500 inhabitants, whether it was in the form of a free secular or a private catholic institution, was a hard-fought victory (Theis, guizot.com).

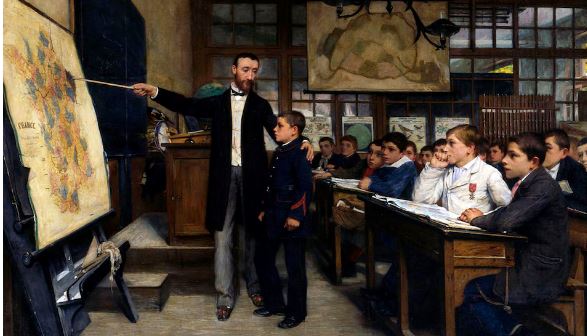

THE BLACK STAIN, BY ALBERT BETTANIER (1887).

For the conservative right, who viewed secular education as nothing more than socialist indoctrination, the church’s limited presence in schools was not a settled issue. So in the wake of the Revolution of 1848, the newly formed, conservative-dominated assembly of the Second Republic quickly passed a new series of education laws. Written by the comté de Falloux, who was the Minister of Public Instruction and Worship, these loi Falloux would greatly expand the role of the church in education. The laws also expanded education to include primary schooling for girls. Communities of over 800 inhabitants would now be required to build schools for girls as well, in addition to those that had already been constructed under Guizot, for boys (in communities of over 500). The ease with which the loi Falloux had passed was made possible both because of the work done by Guizot, as well as because the anti-clerical Republicans now had a minority representation in the Assembly.*

(*) This was the political backlash in the wake collapse of the financial systems across Europe, and the Revolution of 1848, allowing a conservative coalition of monarchists and Bonapartists to power. The short-lived Second Republic of 1848-1852 was headed by President Louis-Napoléon. Napoléon, the nephew of Napoléon Bonaparte, would lead a coup d’etat in 1852 when the assembly tried to block his re-election as president and would pronounce himself as Emperor Napoléon III.

1871: the political fallout of the Prussian’s defeat of Napoléon III

The defeat and capture of Emperor Napoléon III by the Prussians in 1870 and the ensuing siege and surrender of Paris in 1871 left the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate (appointed by Louis-Napoleon) and the National Assembly with the duty of re-establishing a government. All had assumed that France would return to a constitutional monarchy, as aside from the short twelve-year rule of the First Republic and the four years under the Second Republic, France had only known a history filled with monarchs and emperors. Three factions sought their heir to take the throne: the Legitimists (supporters of a Bourbon king), the Orléanists (supporters of the Carpets – descendants of Louis-Philip), and the Bonapartists. The return of a Bourbon to the throne was accepted as the most “legitimate” claim to the throne. Charles X’s grandson, Henri d’Artois, Comté de Chambord had been poised to do so for many years. He had been the “pretender to the throne”, with every regime change, waiting, usually in exile, to be called to his duty. And in 1872, he had come so close to becoming the king of France. Yet his refusal to rule under the tri-colored flag would ultimately cost him the throne (Bicknell 1884). Because while Henri de Chambord saw the tri-color as a bitter symbol of the fall of his family and of the revolution, to most Frenchmen, the flag was a symbol of immense pride and a symbol of French military glory. They would not give up the tri-color, and Henri de Chambord would not be king.

With Chambord out of the picture, a panic set in amongst the Legitimists. In a masterful series of political maneuvers, Adolphe Thiers used the mutual fears of the Legitimists and Bonapartists regarding a successful Orléanists bid for the monarchy. Thiers positioned himself as a preferable pseudo-conservative alternative to an Orléanists usurping power. Despite Thiers longstanding Republican party affiliations, the Legitimists supported his bid for power as prime minister of the new Third Republic. Certainly, his brutal suppression of the socialists in the Paris Commune cemented his reputation as an authoritarian and as a stalwart anti-communist, they allied their fears that they were not putting a staunch liberal into power.

The Third Republic proved successful at maintaining power for the next seventy years. Within the ensuing decade, the secular Republican party would dominate in their legislative control of the Third Republic. Jules Ferry would come into party leadership and ultimately as serve as prime minister for two short stints, 1880-1881 and 1883-1885, yet he would play a pivotal role in the story of français overtaking the many patois as the primary language used in France.

Author’s commentary: Impressive, is despite all of the violent revolutions, and major traumas, both war and political, that have occurred in France, the constitutional government never fell, regardless of some of the regime collapses that it was forced to deal with. The military, too, never forced a coup and seemingly remained obedient to the National Assembly in times of transition. The country never fell into total chaos (depending on your judgment of the ‘Reign of Terror), which can occur with the fall of a primary ruler or a dominant government leader. The National Assembly was always there to maintain order as an “interim government” until it could be decided who would come to power next.

The 1880s: renewed calls for national unity, and new attacks on patois

In addition to holding the position of the President of the Council of Ministers (prime minister), Ferry simultaneously held the position of Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts. It is believed by most historians that Ferry and others in France were so alarmed by France’s defeat at the hands of the Prussians that it was considered imperative that every measure possible must be taken to strengthen and unify the country. A dramatic example of France’s fear of the future was that during this period, French school children were patriotically marched, made to carry wooden guns with fixed bayonets (Gaulupeau 2000).

So it was with this fear of again being conquered that Ferry pushed through a series of strong educational laws in 1882. which, along with making public instruction free and mandatory, divested France of the church’s participation in public primary education.

Republican leadership had always viewed the Church and its teachings as an organ of “superstition and regression” (Zantedeschi undated), but now their desire to rectify this perceived national weakness gave them sufficient justification to pursue a stricter form of laïcité (the absence of religious involvement in the state). That it took ten years for the Republicans to undo the Ferry laws of 1848 probably gives us a good idea of how long it took Republicans to gain majority control over the National Assembly.

Also important was the Ferry laws tightened requirements regarding the size of communities that were required to provide education for their children. From 1882 onward, any village with more than twenty children must provide a primary school education (Zantedeschi, undated). This dramatically spread the reach of education and the teaching of français, far more deeply into the sparsely populated rural regions, where patois still flourished.

As part of Ferry’s political objective of national unity, the education laws reportedly forbade the speaking patois on school grounds. According to Wikipedia: “Art. 30 of Loi d’éducation française: states that “It is strictly forbidden to speak patois during classes or breaks.” I have not been able to locate any additional references to this or any other legal prohibition of patois on school grounds. However, Witold Tulasiewicz and Anthony Adams write in their 2005 book, ‘Teaching the Mother Tongue in a Multilingual Europe’, that Ferry published an open letter to primary school teachers in 1883, calling for the need to eradicate all “local forms of speech, whether languages, dialects or patois.” In Ferry’s words, “…each school had to become a French-speaking colony in a conquered country” (Convey 2005).

This was a letter that Ferry wrote on the eve of his leaving his first ministership in 1881, but the primary focus of the letter apparently was not on patois. Rather Ferry wrote of teaching both moral education and civic education in the enlightenment spirit of laïcité. Once again, among the scholarly writings of Ferry’s open letter of 1883, of which there are plenty, I can find no other which mentions his addressing patois. There is simply a stunning absence of information on this subject.

Shaming may or may not have been an “official” governmental policy, but it is more than evident that shaming existed on a systemic level, within the educational system, and elsewhere. There are hundreds of personal accounts of shaming and corporal punishment of students by both teachers and other school officials. These many accounts readily contradict any lack of official records or scholarly study of the subject.

Wikipedia maintains two pages that cover the repression of patois. One is titled Vergonha and the other is Language Policy in France. Vergonha is the Occitan (Langue d’Oc) term referring to the “shaming” of the patois-speaking population. It should be noted that the lack of scholarly work on the subject causes the Vergonha page to be noted for its need of citations. While a lack of citation is not unusual in Wikipedia, since it is a relatively young resource, I suspect citations in this area will not be forthcoming. After all, as the Vergonha page states, “shaming” is still largely a taboo subject in France.

How long shaming existed in schools may significantly predate the Ferry laws. Vergonha’s page on Wikipedia shows evidence of this. It cites a 2007 book written by professor and historian Georges Labouysse*, “Histoire de France, l’Imposture: The Lies and Manipulations of Official History“. According to this text, in 1845, thirty-six years before the Ferry law, a Breton administrator charged his teachers to put a halt to patois in their schools. “And remember, gents,” the administrator instructed, “you were given your position in order to kill the Breton language.” A second example given by Labouysse happened a year later in the Basque country. Here an administrator reportedly told his teachers: “Our schools in the Basque Country are particularly meant to substitute the Basque language with French…”

(*) Labouysse’s book title does raise a red flag about a partisan agenda. Although his name appears often in a Google search, a Curriculum Vitae does not come up. But neither do I find any accusations of having a particular political leaning, an ax to grind, or having espoused any crazy conspiratorial theories.

Tying this all back to Burgundy: Bourguignon in atrophy

So with the implementation of the Ferry laws of 1881, in conjunction with the systemic use of the shaming and punishment of students by school officials, there was significant pressure across the country not to speak publically in the local patois. It would take less than two generations to cement français as the one language which was spoken almost universally across France. The final nail in patois’s coffin would be the four years that France’s men would spend hunkered down in the trenches of World War I. To paraphrase Eugen Weber, they left for the war as peasants and came back as Frenchmen.

The penetration of français into the more isolated interiors of the country may have been far slower where communities had fewer than 20 school-aged children. However, there were other factors that were putting significant pressure on these regional languages.

The success of a language is all a numbers game, and small rural villages were quickly losing residents for various reasons. The first began around 1820 when birthrates everywhere across Europe began to decline.* This, when coupled with a rural exodus that began around the same time, meant that these communities were taking a big hit in population. This does not even factor in other rural economic hardships which occurred, only one of which was phylloxera. People were leaving these rural agricultural areas leaving fewer and fewer people to speak these languages. By 1988, out of a total population of 1.6 million people who were spread across the four Burgundian departments, only 50,000 people (estimated) had some knowledge of Bourguignon (languesdoil.org).

A 2010 survey done by Les Langues & Vous** revealed (in the map above) the locations and the degree to which patois was still spoken across Burgundy. The darkest spots indicate patois spoken at home, and the red spots indicate that patois was only spoken by elders in that location. The open circles were areas where only français remained (map source: Léonard and Barot 2012)

Léonard and Barot write in their 2012 paper, ‘Language or Dialect Shift? Shifting, Fading and Revival of Burgundian Gallo-Romance Varieties’, that français had infiltrated the Côte more quickly than other provincial regions. This, they claim, was for two reasons, the first of which was the region was covered by a dense network of monasteries. This is at odds with the history given by the University of Ottawa’s Site for Language Management’s suggestion that the church’s teachings in Latin had actually hindered the spread of français.*** Contradictions in the various interpretations of the meaning of history are many.

Léonard and Barot cite a second factor: wherever “mid-sized urban centers” were more closely spaced, français seemed to more easily be able to infiltrate nearby countryside. This may have been a factor. If you look again at the map on the right and trace a line from Auxerre to Dijon, then down through Beaune, you will notice that there are very few remnants of patois.

(*) This is a complicated issue, especially when looking at small villages across Burgundy, which saw population losses of 50% from 1793. This will be the subject of the next article.

(**) I have found no Google reference to Les Langues & Vous, but this is apparently an educational NGO based out of Dijon.

(***) The Site for Language Management, however, did not give a time range for this position, and the period discussed may have been earlier, in the 16th and 17th centuries. Historians do know that one of the major reasons behind the 1539, ordinance of Villers Cotterêts was to restrict the use of Latin, thus the influence of the Church. Thus, intendants and provincial administrators (the noblesse de robe) all spoke in French, and all official business of the state was performed in French. The development of the French language (which I had originally planned to lead this article on patois, was moved to the end and will be discussed in an upcoming article. For better or worse, it keeps getting pushed back as I delve into new issues of how patois was affected by the national economic crisis, demographics, and how they both affected the people of Burgundy.

In Burgundy, français spread along the wine routes

A conclusion missed by Léonard and Barot is that this path between cities is precisely the route first established by the old Roman Via Agrippa from Auxerre to Mâcon. Where Léonard and Barot’s idea falters is that along the road from Beaune, near Cluny, and again near Mâcon, there are still concentrations of patois speakers. This indicates not so much that they are wrong but that there are other factors involved. I believe the major contributor to the growth of français in this area was the influx of money and people involved in the wine trade.

The economics of the region suggests that the transition to français along the escarpment of the Côte d’Or occurred as a natural development. Just as I believe the wine trade had previously spread the patois of chalonnais along the same route, I believe it was the economics of wine which now hastened the spread of français. During the 18th century, with new roads open to the port cities, the wines of Burgundy quickly gained great demand in Holland, Germany, England, and elsewhere. With such demand, prices escalated quickly, many times higher than they had historically been. Wine was now big business in Burgundy. Trade now required communication and contract negotiations with both domestic and international partners, and these deals involved large sums of money. Fluency in français had become critical.

The wine industry was bringing considerable wealth into the renowned villages of the Côte, and it buoyed the fortunes of those who controlled plots in desirable locations, regardless of their social status. Their grapes were now worth more, and because of that, their land was worth more. For these plot holders, there was an incentive to learn to communicate with Francophones, particularly as more and more speakers of français were being drawn into the area, by both the money to be made and the prestige that association with these vineyards brought. For those peasants who farmed the better plots of Gevrey, Vosne, Volnay, Meursault, or Puligny, they would have suddenly found themselves with an economic incentive to learn this language that brought them financial success. A natural decline in the use of patois Bourguignon within these villages was inevitable.

But I believe there were other economic factors that were brewing, which, when combined, would push patois out of the Côte. The old bourguignon dialect of chalonnais would virtually cease to exist with the exodus of the people who spoke it.

Coming up: The effects of the economic crises of 1840, Phylloxera 1850, rural exodus, and the declining birthrate on patois.

References

The Pretenders to the Throne of France, A. Bicknell, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine November 1883 to April 1884

Vernacular culture as a religious rampart: Roussillon clergy and the defense of Catalan language in the 1880s, Francesca Zantedeschi, Spin

Le Monde de l’éducation, Yves Gaulupeau, 2000, cited in From the Schoolroom to the Trenches: Laïcité and its Critics, Ian Birchall, paper given to London Historical Materialism Conference November 2015

Teaching the Mother Tongue in a Multilingual Europe, by Witold Tulasiewicz, Anthony Adams, A&C Black, 2005

Economic, Social and Demographic Thought in the XIXth Century: The Population Debate from Malthus to Marx, Yves Charbit, Springer Science & Business Media, 2009

The European subsistence crisis of 1845-1850: a comparative perspective Eric VanHaute, Richard Paping, Cormac Ó Gráda, IEHC Helsinki, 2006

The Ideological Polarization of Europe in 1792, professor William Patch, Washington and Lee University, http://home.wlu.edu/

Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France 1870-1914. Eugen Weber, Stanford Univ. Press. 1976.

Schooling in Western Europe: A Social History, Mary Jo Maynes, Suny Press 1985

Teaching the Mother Tongue in France, Francoise Convey, Teaching the Mother Tongue in a Multilingual Europe, edited by Witold Tulasiewicz, Anthony Adams, A&C Black,June 9, 2005

Regional Dynamics Burgundian Landscapes in Historical Perspective, edited by Carole Crumle

Languages and the Military: Alliances, Occupation and Peace Building, edited by H. Footitt, M. Kelly, Springer, 2016

Collective Action in Winegrowing Regions: A Comparison of Burgundy and the Midi – David R. Weir July 1976

Language or Dialect Shift? Shifting, Fading and Revival of Burgundian Gallo-Romance Varieties, Jean Léo Léonard & Gilles Barot, 2012

End or invention of Terroirs? Regionalism in the marketing of French luxury goods: the example of Burgundy wines in the inter‐war years, working paper Gilles Laferté Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique

Negotiating Territoriality: Spatial Dialogues Between State and Tradition, Allan Charles Dawson, Laura Zanotti, Ismael Vaccaro, Routledge 2014

‘Insofar as the ruby wine seduces them’: Cultural Strategies for Selling Wines in Interwar Burgundy,” Philip Whalen, 2009

The Abbé Grégoire and the French Revolution: The Making of Modern Universalism, Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall, University of California Press, 2005

From Savage to Citizen: The Invention of the Peasant in the French Enlightenment, Amy S. Wyngaard, University of Delaware Press, 2004

Le patois bourguignon, patrimoine en danger, Arnaud Racapé, France Bleu Bourgogne, 2015

Many histories gloss over the issue of language with no more than an occasional reference to ‘terms’ which were “in the patois of the region.“ This leaves the impression that

Many histories gloss over the issue of language with no more than an occasional reference to ‘terms’ which were “in the patois of the region.“ This leaves the impression that

The economic situation of the chalonnaise speaking peasantry of the Côte d’Or, was not at all uniform. The very poor were likely to be immobile, while those with one or more holdings, particularly if one was in a renown cru, were likely wealthy enough to own a horse, and were able to travel to neighboring towns, perhaps to do business with their négociant, or their tonnelier (barrel maker), or to seek any other service or product that was not available in their own village. Those peasants who were able to travel, spread their sub-regional terms and pronunciations to other villages while bringing new ones back home. This process would have developed a uniform patois, that over time spread over a larger area of use.

The economic situation of the chalonnaise speaking peasantry of the Côte d’Or, was not at all uniform. The very poor were likely to be immobile, while those with one or more holdings, particularly if one was in a renown cru, were likely wealthy enough to own a horse, and were able to travel to neighboring towns, perhaps to do business with their négociant, or their tonnelier (barrel maker), or to seek any other service or product that was not available in their own village. Those peasants who were able to travel, spread their sub-regional terms and pronunciations to other villages while bringing new ones back home. This process would have developed a uniform patois, that over time spread over a larger area of use.